A Brief History of Oregon's Haters

In which some people are very rude about the Pacific Northwest

I am a relative latecomer to Oregon, but I like it here. Sure, it’s a little cold and wet and it gets very dark in the winter, but I like the rain and the summers are very nice. Also, there’s a lot of weirdos here, which I think is neat.

(As I am writing this it is bitterly cold and sleeting outside, but I will not be swayed from my convictions)

In the current-day imagination, Oregon is largely forgettable, rarely relevant on the national stage except when Fox News needs to raise the terrifying spectre of left-wing radicals in Portland or the New York Times wants to point out a failure of liberal drug policy. As it turns out, this isn’t new: our little region has caught a lot of flak from people with very strong opinions about a place most of them have never visited. Let’s review a few of my favorites:

(A quick note: most of these guys are not making a distinction between the eventual state of Oregon and the whole of Oregon Country, which includes Washington and parts of British Columbia, and they probably wouldn’t care to. If you want to hear more about this, come to my talk at McMenamin’s Grand Lodge on March 13th!)

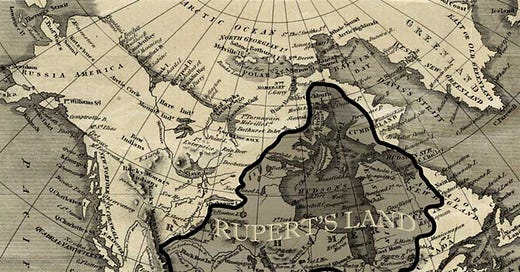

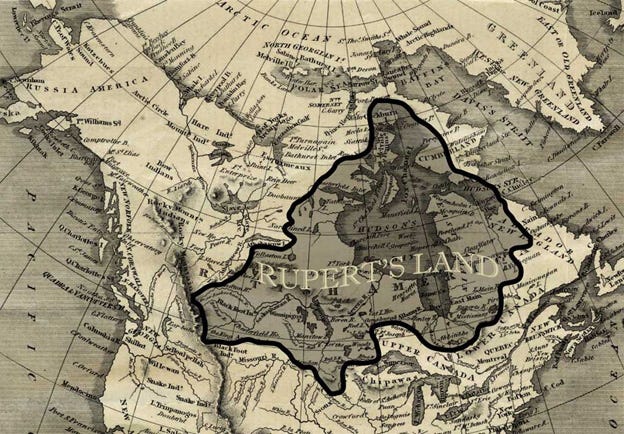

From the early 1800’s on, Oregon Territory or Oregon Country was contested land, claimed by both Britain and America (and, amusingly enough, Spain). This dispute was almost entirely theoretical, as before the 1840s there were, at most, a handful of settlers in the area representing both countries (though the British did seize Astoria during the War of 1812, which proved most inconvenient for John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, but did not seem to trouble the American government terribly).

A couple of loose compromises were laid down, but by the mid-19th century, the question of who would end up owning the Oregon Country and where the line would be drawn came to a head, and men on both sides of the Atlantic decided to weigh in on such questions as: Is this land worth anything? Is it worth fighting for? Where is, Oregon, exactly?

In 1845 a writer for the Edinburgh Review said:

It seems probable - that in a few years all that formerly gave life to the country, both the hunter and his prey, will become extinct; and that their places will be supplied by a thin white and half-breed population, scattered along a few fertile valleys, supported by the pasture instead of by the chase, and gradually degenerating into that barbarian far more offensive than that the savage, which degrades the backwoodsman.

Very rude! The general consensus among the learned classes of England was that the only habitable place in the whole territory was Vancouver island, and that the rest was “a costly, unrofitable, incumbrance [sic]” only inhabitable for a few months out of the year.

A (probably apocryphal) story attributes the following to one Captain Gordon, who led an expedition into the territory: “I would not give one of the bleakest knolls of all the bleak hills of Scotland for twenty islands arrayed like this in barbaric glories!”

Another writer said that Oregon “contains detached portions of good land, but these form the exception and not the rule…there is no promise of any productive article of export.”

Tell that to our bustling industry of artisinal hot sauces!

As the question of compromise came to the fore in parliament, the Niles Register pushed for a deal, saying that “So favorable an opportunity must not be thrown away, for a punctilio, or a barren waste of Northwestern wilderness.” There was not universal agreement about the value of the area, but in the end the British were willing to let a very large portion of it go for little more than a gentleman’s agreement to not agitate further and some trade concessions.

If you thought only the British had such vitriol for the great Pacific Northwest, you thought wrong! Despite the popularity of the call of “Fifty-four forty or fight!” (claiming the border as far north as Alaska), American politicians were not enthusiastic about Oregon Country. Senator George McDuffie of South Carolina once said that he would not “give a pinch of snuff for the whole territory” and Senator Jonathon Dayton of New Jersey said that “the whole country was as irreclaimable and barren a waste as the Sahara desert”, which seems like a slight exaggeration but, with respect to the Senator, I’m not sure he was operating with a complete picture of the area.

Even President John Tyler’s Secretary of State, the esteemed Daniel Webster, said that Oregon was “a barren, worthless country, fit only for wild beasts and wild men”, though he would later reverse course on this.

Now, to be fair, there were also men that made glowing pronouncements about the glorious potential and productivity of Oregon Country, but the general mood in the 1800s was that it was a desolate place and very far away and not worth the trouble of fighting for.

An important question (and likely the subject of a future newsletter) is to what extent this was, for lack of a better word ‘cope’, men making excuses for having to give up territory, and how much of it was genuine conviction informed by facts.

In any case, the haters can go kick rocks, I think it’s a pretty swell place.

Sources:

Commager, Henry. “England and Oregon Treaty of 1846.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1927): 18–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20610369.

Scott, Leslie M. “Influence of American Settlement upon the Oregon Boundary Treaty of 1846.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 29, no. 1 (1928): 1–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20610404.