Today is the first Sunday after the Paschal full moon, which means it is Easter Sunday. If, like me, you were a pretty ordinary middle-class American kid, you probably mostly remember this day for its middling pastel candies, fancy and uncomfortable outfits, Easter egg hunts, and a lot of people saying “He is risen” at you.

If you’ve spent much time listening to me talk or reading this newsletter, then you know that I enjoy digging into the history of our shared holidays, especially the ones we tend to take for granted. With the big religious ones, this probably stems from a teenage edgelord phase where I delighted in annoying everyone around me by telling them about the pagan origins of certain Christian traditions, but now I just think this kind of thing is interesting.

Easter is, of course, the Christian festival celebrating the resurrection of Jesus Christ following his crucifixion, and it comes on the tail end of the 40 days of Lent, which in turn observe the 40 days that Jesus spent fasting in the desert. It is a ‘moveable feast’, with a devilishly complicated date to calculate, but it always happens shortly after the spring equinox. Easter also sometimes overlaps with Passover, which celebrates the angel of death passing over the Israelites in Egypt (but also maybe it’s even older than that).

There are also many ancient celebrations of the return of spring that included themes relating to death, rebirth, renewal, so on and so forth, that occur around this time, and over time a lot of these different traditions have gotten rolled up into the general springtime Easter festivities.

If you go poking around in certain corners of the internet, you might come across a post claiming that Easter is actually a celebration of the Babylonian goddess Ishtar and that Constantine (or some other church father) appropriated the holiday for the resurrection.

As entertaining as this theory is, there is, unfortunately, not even a hint of truth to it. Ishtar is not pronounced Easter and while Ishtar’s portfolio has a little overlap with some Easter traditions, that’s kind of where it ends.

There is, however, perhaps some truth to the claim that Easter is an appropriation of an earlier pagan tradition. We have church records of Easter celebrations dating very far back, at least to the second century, but it is plausible that the date was chosen to coincide with existing pagan celebrations.

You might be forgiven for thinking that this idea is a new one, the product of a decaying society and fraying social mores, peddled by exclusively by new age wackos and militant atheists, but that’s not the case! Before a bunch of megachurch weirdos hijacked the conversation and made Biblical literalism a bedrock doctrine of American Christianity this kind of claim used to be relatively commonplace (if not uncontroversial) — James George Fraser wrote about it in his influential (and spicy) 1890 book, The Golden Bough:

Thus it appears the Christian Church chose to celebrate the birthday of its founder on the twenty-fifth of December, in order to transfer the devotion of the heathen from the sun to him who was called the Sun of Righteousness. If that was so, there can be no intrinsic improbability in the conjecture that motives of the same sort may have led the ecclesiastical authorities to assimilate the Easter festival of the death and resurrection of their Lord to the death and resurrection of another Asiatic god which fell at the same season. (Fraser, p. 359)

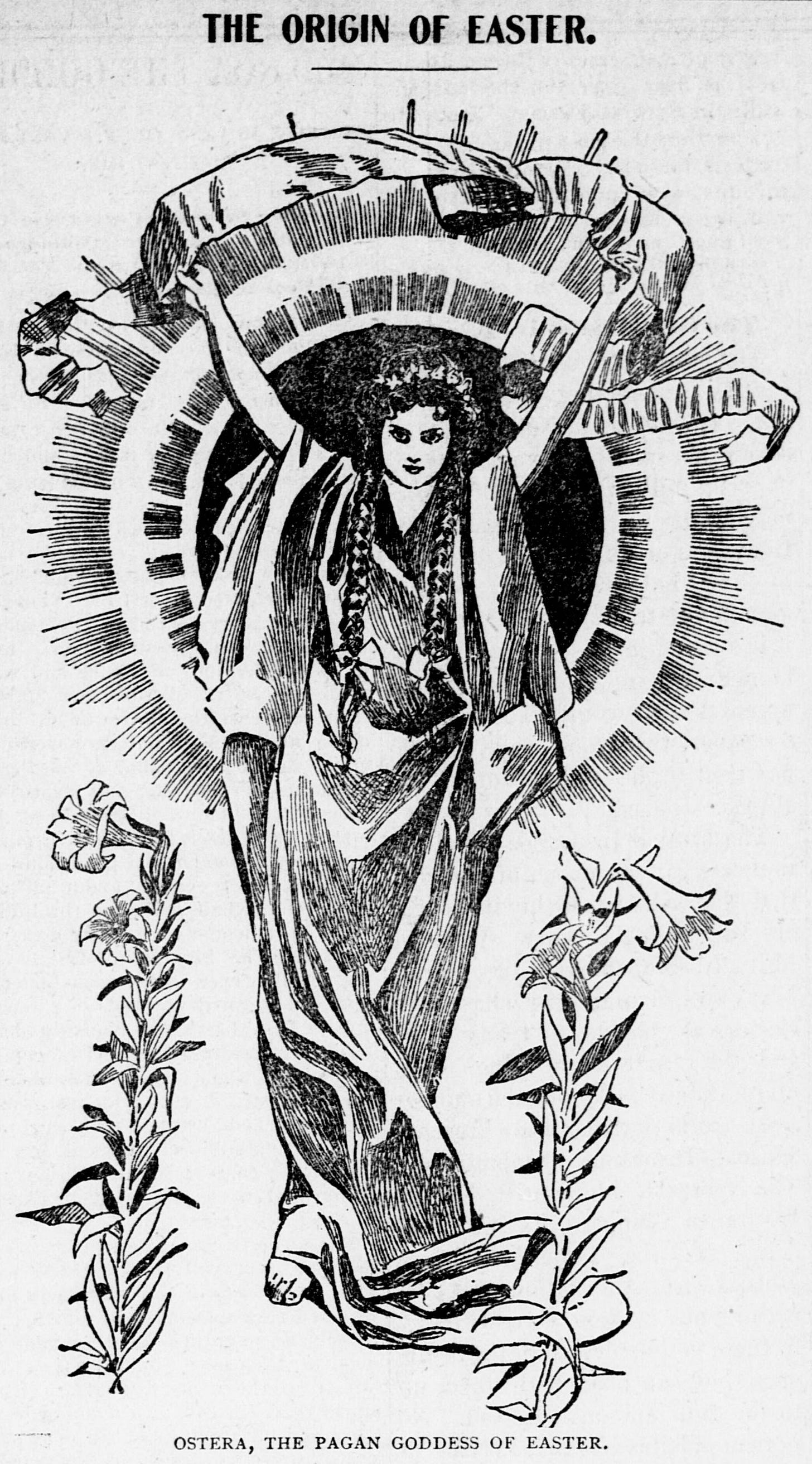

The “Asiatic god” in question was not actually Asiatic at all, but a Germanic goddess called Eostre or Ostara, and the further truth is that we don’t know very much about her or her worshippers at all.

Eostre was an Anglo-Saxon diety of the springtime, possibly associated with the sun or with fertility, who was honored with feasting around the time of the spring equinox. According to ancient sources, the Anglo-Saxons observed a month called Ēastermōnaþ (something like Ôstarmânoth in Old Germanic), during which, presumably, an Easter festival of sorts occurred.

This is where I reveal that I’ve deceived you a bit, because when I said “ancient sources” what I actually meant is “ancient source” because almost everything that we know about Eostre comes from exactly one person: the Venerable Bede, an English monk and scholar responsible for several important works of history, including De Temporum Ratione (The Reckoning of Time), where he records this about Eostre:

Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated "Paschal month", and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance

Congratulations! If you read that quote in full you are as close to an expert on Eostre, goddess of the dawn, as anyone in the world, because that is all that was written about her for thousands of years.

This is where it gets interesting to me, because as you can see above, there was definitely an awareness of Ostara/Eostre and the potentially pagan origins of Easter as far back as the turn of the 20th century.

Ordinarily there are a lot of different explanations for an idea like this entering the public consciousness, but in this case, it appears that there is a single point of inception, and that is a book by Jacob Grimm (yes, that Grimm) called Deutsche Mythologie (1835) which takes Bede at face value and associates Eostre more generally with a broader Germanic goddess, Ostara (who Grimm may have made up).

This idea of Eostre is repeated in other books on mythology and paganism throughout Europe for the rest of the 19th century, and from it emerge all manner of interesting and bizarre ideas (the Easter bunny, for example, is a real headscratcher), but the root remains Grimm, and through him, Bede.

As you may or may not know, Victorian Britons were absolutely fascinating by all manner of paganism, spirituality, and the occult (this is the time of Aleister Crowley and high-society seances), so it comes as no surprise that they unearthed this tidbit about Easter and spread it widely (much to the shock and chagrin of the church). From there, the so-called pagan origins of Easter entered the greater discourse and every year, like Christ himself, they rise again.

References:

Barnett, James H. “The Easter Festival--A Study in Cultural Change.” American Sociological Review 14, no. 1 (1949): 62–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/2086447.