In 1845, a twenty-five year old Friedrich Engels was living in Manchester, working in his family’s cotton thread factory — this was, for reference, before his magnificent beard and before his key collaborations with Marx. At a relatively young age Engels had begun reading Hegel and other German intellectuals and had developed some radical views that distressed his wealthy parents, so after he served his required time in the Prussian army, he was sent to work in Manchester, presumably with the hope that it would temper his extremism. Unfortunately for ma and pop Engels, it appears to have had the opposite effect.

While in Manchester, Engels took up with an Irish firebrand named Mary Burns, and through her and through his own investigations, got a firsthand look at the misery that was being inflicted on the English working class, which prompted him to write a book on the issue, The Condition of the Working Class in England.

In this book, Engels coins the term “social murder”, which he defines thusly:

When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission.

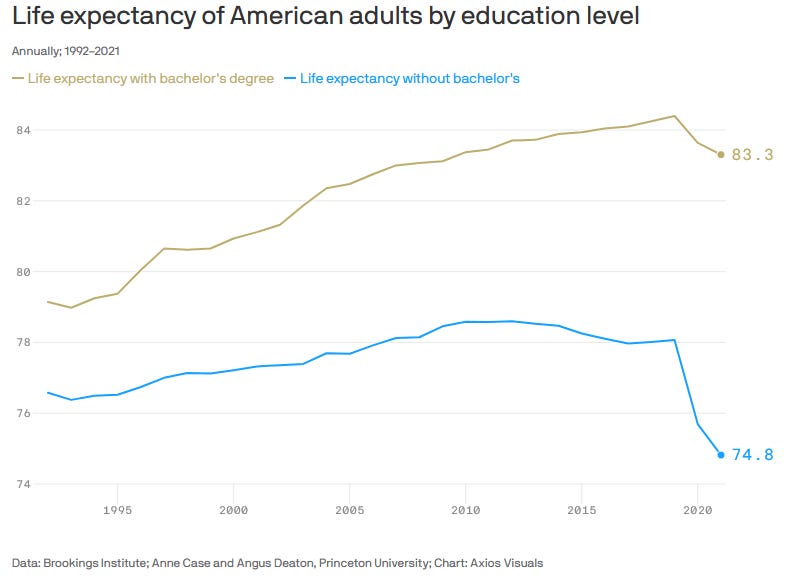

This is, I think, a very useful idea, and also one that has seen a resurgence of interest in recent years. It has been used recently in England to describe the deaths of seventy-two people in Grenfell Tower, an accident blamed largely on government cost-cutting and neglect, and is seeing use as a way to describe the consequences of decades of austerity in western nations and explain the rise of deaths of despair.

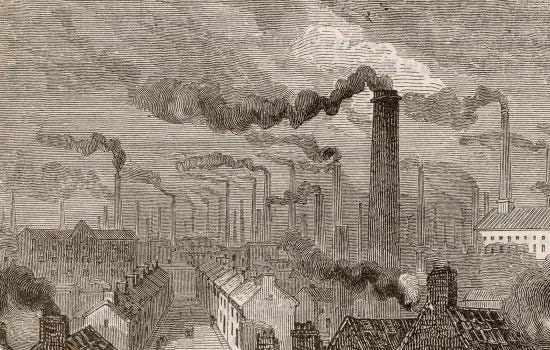

There are a lot of interesting (and depressing) parallels in Engels’ book that I think are worth revisiting at this moment in time. He identifies a host of problems afflicting the English working class, but three in particular stand out to me. Engels’ describes the filthy environment of English cities thusly:

They are drawn into the large cities where they breathe a poorer atmosphere than in the country; they are relegated to districts which, by reason of the method of construction, are worse ventilated than any others; they are deprived of all means of cleanliness, of water itself, since pipes are laid only when paid for, and the rivers so polluted that they are useless for such purposes; they are obliged to throw all offal and garbage, all dirty water, often all disgusting drainage and excrement into the streets, being without other means of disposing of them; they are thus compelled to infect the region of their own dwellings.

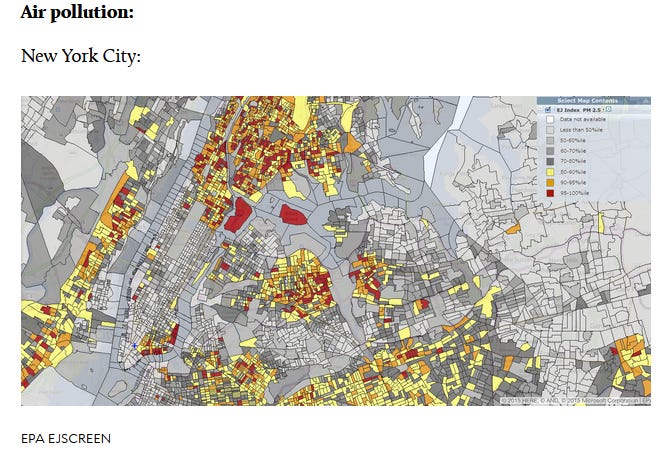

We have come a long way from the polluted and disease-ridden cities of the industrial revolution, where cholera and typhus and tuberculosis ravaged the working poor, but one thing that has not changed is that the poor of this country (and more especially, the world) are exposed to pollution and toxic substances and other environmental hazards at a massively higher rate than the rich. The EPA maintains a number of tools that let you sort high-pollution areas by income and demographics and the results are more or less exactly what you’d expect. People living in poorer parts of the country have higher rates of asthma, certain types of cancer, emphysema, and other maladies caused or exacerbated by the environment.

Engels goes on to mention how the working class has come to depend on alcohol and other vices just to survive the day:

The working-man comes from his work tired, exhausted, finds his home comfortless, damp, dirty, repulsive; he has urgent need of recreation, he must have something to make work worth his trouble, to make the prospect of the next day endurable…His enfeebled frame, weakened by bad air and bad food, violently demands some external stimulus; his social need can be gratified only in the public-house, he has absolutely no other place where he can meet his friends. How can he be expected to resist the temptation? It is morally and physically inevitable that, under such circumstances, a very large number of working-men should fall into intemperance.

In the 21st century those deaths of despair I mentioned — suicide, overdoses, and diseases caused by drug or alcohol abuse — fall most heavily on the working poor, who are maligned, abused, and lectured for their dependence on alcohol or fentanyl or other opiates, even as these things are aggressively pushed on them by corporations seeking more customers and higher profits. Though comparatively the modern working class has more material wealth than a Manchester factory worker could ever dream of, they share the same social contagion.

Engels also brings up the lack of medical care available to the workers of the city:

English doctors charge high fees, and working-men are not in a position to pay them. They can therefore do nothing, or are compelled to call in cheap charlatans, and use quack remedies, which do more harm than good. An immense number of such quacks thrive in every English town, securing their clientele among the poor by means of advertisements, posters, and other such devices.

Medical science was far less advanced in Engels’ Manchester, but there were doctors, or medical professionals at least — these services, however, were not the kind of thing that an ordinary person could afford, and a special kind of product emerged to alleviate the many pains and maladies caused by miserable living and working conditions.

Pills, cordials, tinctures, and other remedies took off in this period, and they were generally either complete snake-oil or simply opiates (laudanum) in a flashy package. Hey, did you know that dietary supplements are a 53 billion dollar industry and are almost completely unregulated by the FDA? Just a neat little fact that I thought I’d throw out there.

It’s Still Murder if You Do it With a Spreadsheet

So, you might have guessed that the underlying impetus for this newsletter is the violent murder of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson yesterday (December 4th). Though the motive for this murder remains unclear at the time of writing, the police have recovered shell casings at the crime scene that read “deny, defend, depose”, referencing a common series of tactics used by health insurance companies when denying claims, so I think maybe we have some idea of what’s behind it.

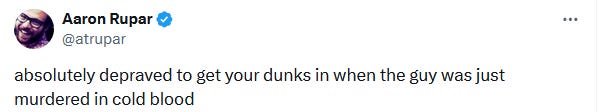

I’m not going to weigh in on whether or not this is a good thing (that’s a different newsletter), but there are a lot of people speaking up on social media celebrating the attack. There is clearly a lot of pent up rage about the US healthcare system looking for an outlet, and some people are reviving the idea of social murder as an explanation.

It is estimated that between 20,000 and 50,000 Americans die every year because of a lack of health insurance — there are still somewhere around 30 million Americans who are uninsured. Depending on your perspective, many deaths that we accept as the cost of doing business are preventable, but these are more preventable than most — the care they need exists, but they cannot access it. These deaths are, in Engels’ view, not tragic accidents, but deliberate murders. I think this is a valuable viewpoint.

When a health insurer makes the decision to deny a claim, or more broadly, to deny a whole category of claims, or drop coverage for expensive customers, or implement policies that deliberately make it harder for people to access care, those decisions result in sickness, death, and misery. The responsibility, is, perhaps, distributed within the company, but the idea for these decisions and the impetus to act did not emerge from the ether — someone had to design and sign off on these strategies. People are dead who might otherwise be alive, whose deaths could easily have been prevented, and in a just world, someone would need to answer that. A CEO is perhaps a good place to start assigning responsibility, but almost certainly not where it should end.

I originally intended this newsletter to mention other forms of social murder: deaths caused by climate change, government repression, lax regulations across a host of industries, etc., but I’ve gone on long enough. I’ll talk especially another time about a form of social murder that is personally very important to me: accidental drowning, which kills the children of the poor and minority communities at vastly higher rates than rich white children.

The pearl-clutching response of some members of the centrist commentariat about the murder of Brian Thompson suggests that they either do not understand or are choosing not to understand this point, but you don’t have to be an arch-socialist like Engels to understand how deaths of neglect, deaths of omission, are still murders. Mark Twain wrote the following in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court:

There were two “Reigns of Terror,” if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror—that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves

Over a hundred years later we have still not been taught to see that, but maybe we are starting to.

I hope you take this newsletter in the way that it’s intended — not that we are still fighting the same battles two centuries later (true), but that our forebears are part of the same struggle, the same fight for justice, and that we can lean on them for inspiration and support.