The historian cannot choose to be neutral; he writes on a moving train." - Howard Zinn

(NOTE: This and a few other newsletters were originally published on another platform back in 2020, I’m going to be revising/updating and republishing them since they feel eerily/depressingly appropriate for the present moment).

As we stare down the barrel of a second Trump presidency (and the general rightward turn of the country as a whole), I thought it would be instructive to tell you (and remind myself) why I think this is worth doing. To be clear, I’m not under any illusions about my impact or influence (which is small), but I am more convinced than ever that the work of talking about the history of radicals, of the working class, of the disenfranchised, is worth doing.

In times like these I think it’s important to continue to engage with your community and continue unapologetically doing the things you love, so I’m going to be doing more talks, but also more newsletters, more TikToks, and possibly podcasts/videos if I have the time and inclination. If that sounds cool, make sure to subscribe — I’ll even have some subscriber only content for you superfans.

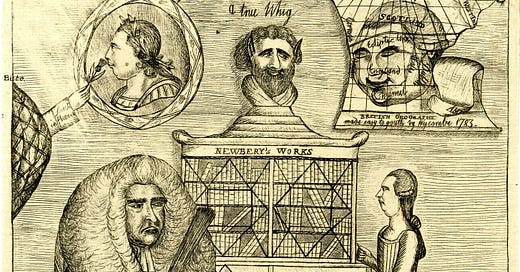

Much of the older generation, probably as a consequence of having spent their lives in a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity, are largely still in the thrall of a Whiggish historical narrative, where America is on the right side of every conflict and, though perhaps imperfect, always working toward justice. Worse maybe, younger Americans who are interested in history are learning it through historical video games, memes, and social media (there’s nothing inherently wrong with any of things, but I know what grade school history curriculum looks like, so they certainly aren't learning it in school), or they're getting their information from the likes of Joe Rogan or Prager U or Ben Shapiro, which riles me up to no end. I've been encouraged by the proliferation of information on Twitter and TikTok and elsewhere that challenges the status quo, but the brave teens who dance and talk about CIA coups are fighting an uphill battle.

History is never neutral. It is, by nature, the work of crafting a narrative and a way of understanding the past. That does not make it 'false', and it does not make attempts to correct mistakes 'revisionism'. History is a living discipline, but there is a subconscious bias toward making it seem dead, settled, and irrelevant, but it is not. You can draw direct lines from the events of the past to the problems of today, and pretending otherwise serves no one but the powerful.

Fifty years ago Howard Zinn asked the question "What is Radical History?", which is partially why I decided on this as a name for my channel. He makes the case for a "value-laden historiography", saying that we should pursue history with a deliberate aim of fostering racial, national, and class equality. I agree with him.

Zinn has a complicated reputation among historians. His explicit project of challenging the prevailing narrative in A People's History of the United States rubs even left and liberal historians the wrong way -- one should strive to be, if not objective, fair and accurate, and though I love it and think it serves an important purpose, A People's History makes some factual and analytical errors that weaken the project overall.

Which highlights a challenge of doing history this way. If you are going to challenge the established order, you must be smarter, better, and more accurate than the stolid defenders of the status quo. It makes no difference that Prager University peddles obvious and blatant propaganda rife with factual errors and clear bias — it’s materials have still made it into the curriculum of at least six states.

This is obviously an ideological project, but if the left (or heck, even the center) tries to play the same game, we get bludgeoned for it. This is why I think we need to start being unapologetic about telling a different type of history.

By simple inertia, any historical consensus often goes unexamined — it is simply the way that things are, and therefore cannot be changed. But this is an indefensible position — every child that goes hungry or every person that dies of inadequate healthcare is a deliberate casualty of a system that has decided that these are acceptable losses. It may be that this is the best of all possible worlds, but even so, those who are satisfied with the state of the world should still be forced to defend it, lest they get complacent.

There is much disagreement on this point, but to me, and to many others, the role of the historian is to discomfit the powerful, to lay bare the inequities and inconsistencies of the world, and to challenge everyone to think critically about how we relate to each other and construct our societies. The root of this discipline is conservative, in finding a justification or explanation for the ordered world that the modern nation-state had created, but it does not have to be so, and this was never a comfortable position for a historian to be in. The past is complicated, and always has been, and just because it does not readily provide easy answers does not mean that there is no value in trying to better understand it. And if what we find doesn't match with the carefully crafted narrative that we have been presented with, then it is incumbent on us to reexamine our positions and review our biases.

Most of all though, what fires me up, what inflames my soul, are those that came before who fought for us, to make a better world, and who have been written out of the histories. Our history books are full of, at best, complicated men, champions on one hand of liberty and freedom, and on the other, willing perpetrators of racial and class violence. Those same books elide and obscure the lives of the heroes who bled and died and stood up to the clubs and bullets of police and private security forces, hoping beyond all reason that they could win a victory for the working class, or make the world safer for future generations. People like Eugene Debs and Rosa Luxembourg and countless organizers and strikers whose names and lives have been lost to time, to whom we owe a great debt, and who suffered, willingly and deliberately, so that future generations could live in a more just world.

To that end, Zinn argues in "Radical History" that one role of the historian should be to show how the world could be different than it is — better, even. When I look to the Paris Commune, or the radicals of Spanish Catalonia, or to the powerful camaraderie of the early worker's movements here and abroad, I see glimmers of how the world could be, if we wanted it to be.

I make no secret of my politics, and I couldn't even if I wanted to, but it is my hope that even if you find me to be too radical or too left, that my point of view can still be interesting and valuable. Just as I try to treat the opinions of conservative intellectuals or defenders of the status quo as valid, even when I disagree, I am hoping that people can and will view my talks and newsletters as reasoned arguments for a different understanding of both the present and the past. You don't have to agree, necessarily, with the solutions that I would hope to implement to acknowledge the historical grounding of the problems I have identified, and the fact that it, quite simply, does not have to be this way.

Most academics find this kind of deliberate partisanship distasteful, and in a perfect world, they would be right to keep their politics and their scholarship separate, but this is not a perfect world, and remaining silent while the world at large twists the narrative to hide the complexities and imperfections of the past serves only to embolden them. As always, I can’t help but return to this quote from Marx in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte :

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.